|

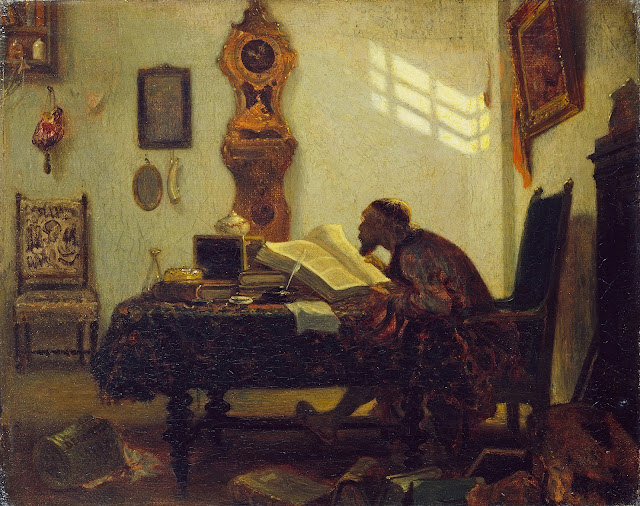

| Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps |

(This entire thing actually came from me learning about Ladino, which is to Spanish what Yiddish is to German, and as I had recently written a Spanish-coded character in Amelia, I though I might as well combine the two. That and I have a great appreciation for elements of Jewish philosophy and their inclusion in MSF is a bit overdue.)

(Many thanks to good friend S.J., who provided a great deal of extremely valuable inspiration and feedback.)

The Followers

The Okavim have a very long history. In the time of the First Empire they were a loose alliance of seminomadic hill tribes, coastal city states, and oversea trading posts - not politically unified, but sharing enough similarities between their cultures that they would side with each other more often than not in opposition to the great kingdoms that surrounded them. Warriors, mystics, and sailors, was the stereotype (as far as the few surviving contemporaneous texts mentioning them go), sitting at the junction between empires.

When Darvatius came, the Okavim fought against him and for him in equal measure. The trade network had brought in iron, and that meant iron chariots, and emperor's legions did not expect to fight anyone who also possessed them. And so his armies bled out in the desert for years, eventually finding it more convenient to turn the Okavim against their local rivals than to conquer them directly.

When the First Empire collapsed and the world slipped into madness, the Okavim scatted to the compass winds as a people in diaspora. Those that survived the Years of Chaos to see the rebuilding of the world did so as a people transformed: the many tribes and groups of their parent culture had coalesced around a new religious tradition, which had just as soon dispersed back out into the world through the remains of the old trade network.

In the modern day, as it has been for centuries, the Okavim are divided into two main culture groups - the Bnei Hayam ("Sons of the Sea"), and the Bnei Haaretz ("Sons of the Earth"). Some outside scholars will use the terms "Maritime" and "Diasporic" to describe the two groups, which is functional but are becoming less used in favor of the endonyms.

The Bnei Haaretz compose the more numerous half, and their communities can be found in any city of decent size on or near the Mare Interregnum. These communities have undergone further diversification over the centuries with the influence of their neighboring cultures so that, while each is recognizably Okavim and participates in the shared cultural continuity, they are by no means interchangable (Acephavaran Okavim are not Arivienner Okavim are not Orleian Okavim are not Eostremontane Okavim are not Amdalani Okavim, so on and so forth). Much of the development in Okavim religious thought comes from Bnei Haaretz communities and the exchange of ideas between them.

The Bnei Hayam live a migratory existence across the Mare Interregnum and throughout the Belt. Most of their cultural exchange has been with the other sea peoples - the Belt Lilifio, the Amazons and Okeanides, the Jahali, the Ksiqua, the Ifeh, the Du and others - and they retain some elements of their pre-diaspora traditions. The ancient veneration of Bhâl-Deghon - a god of fishermen, sailors and weather-workers - was adapted into a mythic non-divine culture hero (drawing from the Belt Lilifio tradition of the demudem). Pouring grog oversides, line-crossing ceremonies, painting wrestling octopi on the sail, spritzing the bow with saltwater and lime juice, that's just traditional.

Avodat

Okavim religion stands out among the practices of the world. While henotheism is common enough (so many gods, so little time; it pays to focus your attention), there are very few cultures that hew to it so closely as to bypass the gods altogether.

(In technical terms, which are less useful when you want to get away from pithy summaries, Avodat would be a monotheist (or otherwise extremely henotheistic) panentheism with strong mystic, esoteric and academic traditions)

Some concepts worthy of pointing out:

The Books - A semi-mythic history of the Okavim, beginning in the land of Daro and continuing up through the collapse of the First Empire, codified during the early Years of Chaos as a way of maintaining cultural unity and continuity through the diaspora. The Books are both one of the first written religious traditions and one of oldest surviving cultural institutions in the world, and have in the millennia since their writing, accumulated libraries-worth of commentary and analysis.

The Light Without End - The divine principle in Avodat belief sustains and empowers the universe through emanation, suffusing the universe with its presence while simultaneously existing beyond it. This is similar to the beliefs of the Solar Church, the Atûmaics, and the mystics of Se Tolahi, though with some critical differences.

- The Solar Church directly associates this divine principle with the sun, and consider it the source from which the gods draw their power; Avodat grants no special spiritual position to the celestial bodies and do not consider the gods to be independent entities.

- The Atûmaics believe that the divine principle has been obscured from recognition by another force, and that the means of ascent to it has become corrupted and dangerous. The quest to reach the realm of true Atûm from the depths of its shadow is a paradoxical, impossible, violent, and necessary task; Avodat does not believe in a antagonistic obscuring force between humanity and the divine (except, perhaps, human ignorance) and holds that the the great divide might be bridged through study and contemplation rather than spiritual warfare.

- The mystics of Se Tolahi... I haven't given enough thought to their beliefs yet, other than they might be monotheists by way of pantheism. I'll get to it eventually. Whatever the case is, the Okavim do not agree with them on the nature of divinity and its relationship to the world.

The Unnamable Divine - Avodat is explicitly aniconist. The divine presence is indicated in art by empty space; in text, it is referred to either by titles or by a series of seven null characters. Anthropomorphic depictions or descriptions are forbidden; lower spiritual principles are often portrayed with symbolic geometric designs.

The Desert Council - A crucial event in the development of Avodat; as portrayed in the Books, a group of seventy-two mystics convenes to determine a worthy god for the Okavim to follow. After long debate they find themselves unable to come to a conclusion, dissatisfied with all the gods that have been proposed. While the historicity of the event is debated, it is emblematic of the shift from typical anthropogamist beliefs towards a system recognizable as Avodat.

The Teaching Hall - An Okavim community is built around its Teaching Hall, where services are held and religious schooling for both children and adults is found. Okavim tradition holds the divine as a mystery that might be discerned - not solved, but endlessly interpreted for its guidance - and so there has been for ages a great focus on continuing education throughout life. Who knows what new insights might be found when new minds are given the tools to discern for themselves?

The Repair of the World - A key component of Avodat is the idea that the world remains in the process of formation, and that it is the responsibility of the Okavim (and, indeed, of the morally upright among all peoples) to work towards the improvement of the world as a whole (care for the sick, hospitality to the stranger, charity to the poor, resistance to the tyrant, and so on). The existence of Hell is, naturally, the Great Test - the last challenge to overcome, the final wound in the world.

Relations with Other Traditions - Okavim attitudes towards the worship of other gods varies, even within the Books themselves. At most conservative interpretation (held now by only those who take on extreme isolation from the world), they are considered wholly false and their veneration is in grievous error. The mainline modern view is as follows: The Gods of Man are representational of lower emanations of the divine principle - instrumental spiritual forces of repair or testing rather than entities in themselves, their human forms an interpretive affect of the worshipers rather than a fundamental truth of the divine. Other peoples may venerate them as they see fit, as they do not bear the same responsibility that the Okavim have assumed with regards to interpreting greater mysteries.

This does not put the Okavim as opposed to their neighboring polytheists as one might expect - anthropogamist traditions trend heavily towards praxis over dogma and practical ethics over metaphysics, and so there is little competition over who gets to define how the cosmos operates - the two traditions are focused at entirely different spiritual aspects of the universe, and unified in most worldly matters.

(There is, indeed, a pair of stock characters in Lower Arivienne comedies who exemplify this relationship - an Okavim student (eccentric and head-in-the-clouds) and a Low Country witch (rustic and salt-of-the-earth), who regularly find themselves preparing for an argument over how to respond to whatever situation is at hand, and then realizing, through a series of humorous miscommunications, that they actually had come to the same conclusion from different routes.)

This rough complementarity, combined with the significant overlap in practical ethics between the two traditions (the Repair of the World meshes nicely with the Great Dûn and Wrath-Against-Injustice), leads to a pragmatic co-existence. When Hell is your enemy, the eccentricities of your neighbors are of little account (indeed, Okavim communities up and down the Arivienne provided vital support to the Maid's forces during the War of the Bull). This attitude did not emerge overnight, but has proven a long-term success.

More contentious relationships exist with the Solar Church and the Atûmaics, given the relative closeness of their cosmologies. There's a long tradition of philosophical pot-shots taken between the parties, and the disagreements can get quite animated.

Local spirits are offered their due hospitality and reverence, but in a more transactional manner than most neighboring cultures. The lack of ceremony can seem offputting to neighboring groups, but practicality works out: if it works, it works. Not getting eaten by an angry river spirit supersedes precisely how you stay on its good side.

Golems - If one knows nothing else about the Okavim, they know them for their golems.

Life-Into-Clay

The making of golems is not a simple task, and not one undertaken lightly. The art of imparting true life to clay is learned only by master sages among the Bnei Haaretz, perhaps only one or two in a generation, and even their knowledge of the art is kept secret unless there is great necessity. In such times when an Okavim community is endangered by threats it cannot defend against on its own - war, wizards, or monstrous beings most often - those great sages will raise a protector, bringing a divine spark in imitation of the divine emanation,

A golem is a singular being, each as unique as the river that supplied its clay and the community that it protects. Some are swift and narrow, some are vast and slow, some will speak with great eloquence and some will remain silent. All of them possess untiring strength and a soul of such raw power that they are near-immune to all magic worked against them.

But clay shaped by human hands cannot contain a soul-flame of such magnitude forever. Golems that remain active for too long will go rampant as their soul strains against the words that keep it bound in clay, lashing out in violence at the communities they once protected. Maddened golems are not invulnerable, but are so strong that more often than not the hand of its maker will be needed to undo its bindings and return it to the earth.

Those golems that recognize the early signs of rampancy will wander out into the wilderness alone, in order to spare humans from their madness. There their fires will fade out, and their bodies will be broken down by wind and water and the roots of growing things. The place where a golem returns to the earth remains holy ground, and the place retains an ember of the soul that once was. Often their makers will choose internment nearby, as penance for their part in bringing these doomed lives into being.

Once there was a wizard who hoped to steal the art of golem-making from the Okavim sages, who desecrated a golem's death-place and used the soil to build his own clay man. No one, not even the most amoral of sorcerers, has ever tried to do so again. Homunculi servants will suffice for the world's wizards; their flames are cool and dim, embers compared to the fiery souls of humans and the great furnaces of golems, and thus stable and easy to control.

Good Brother

Eighteen golems were raised during the War of the Bull, most fighting along the lower Arivienne. Good Brother is the last: indeed, he is the oldest golem ever recorded. Where the others either fell in combat or went out into the wilderness when their time was up, Good Brother has fallen into quiescence. His soul has cooled to embers, stirring to life only rarely. He has not moved in nearly a century, such that a great tree has grown into and around his body. Children play around and on top of him, at his permission ("Do not send them away" he told the site's keepers some decades ago - the longest statement he has said since beginning his slumbering years). A steady train of historians and Okavim pilgrims come to visit him, hoping for a word or two of wisdom or an insight into the past - He is indeed among the few remaining souls who remember the War first-hand.

His most noteworthy accomplishment in the war, and the source of his name, comes from his participation in the liberation of Batlian. He and another golem ("Old Gravel-Face") ended the siege nearly on their own by tearing down the main gate and then using it as a shield for the soldiers. In the days following the battle the Sable Maid arrived with reinforcements, and was seen to leap off her horse and run over to the golem. Embracing him and kissing his head, she exclaimed "Ah, bon frere! How magnificent you are!"

Good Brother was asked often about her, in the days before his quietude. "I loved her," he once said. "So did we all. It is a great curse to be one for whom men will die gladly. I do not know how she bore it."

It is said by some, though never in public, that Good Brother's life has been extended by grief - by his hopes that someday he might see her ride over the hill once more, and trace the scars on her face again, and hear her laugh a last time before he dies.

Ha! Got it done before Hanukkah ended after all.

ReplyDeleteI myself am not Jewish, but the classes I took in college on the development of Jewish religious / philosophical thought have remained an enormous influence and I'd call them one of the best choices I've ever made.

The adaptation to MSF was tricky - monotheism is difficult in a setting where the gods are real and the local nature spirits are a concrete fact - but I am happy with the result. Adding in some influence from the Phoenicians and with the fuzzy henotheism of pre-Exilic Judaism was a good move. The strict "no religious violence" rule in the MSF backend likewise meant I could - had to, really - focus on the elements that are not simply replicating the relationship of Judaism and Christianity through the Middle and Modern ages in a a vague fantasy context. There's more than enough of that in fantasy fiction.

(Related: it is /astoundingly/ difficult to find good art of golems - practically everything's just a World of Warcraft ripoff, if the search function even bothers to give you a golem in the first place. While Decamps' legacy is pretty rocky, I do love that piece up top, though if anyone has a better one I am all eyes. or good golem art)

So I wish everyone reading happy Hanukkah, merry Christmas, joyous Yule, festive Saturalia, or just a good weekend. Keep warm out there, keep safe, call your grandma.

I liked this. The golems are very sad, in a good way.

DeleteIs the "no religious violence" rule just creator fiat (completely valid, if so!) or is it an outgrowth of in-setting material? "Hell is real and you can point to it on a map and materially, verifiably describe its goals" definitely feels like the sort of thing that could take the steam out of a lot of religious persecution. (I would also imagine that, in a world where the gods and spirits are just as verifiable as Hell — more verifiable, even, since you don't have to travel so far to see them for yourself — any "religious conflict" might be better understood as a weird sort of political conflict)

It started with fiat, but then swiftly turned into "okay, so why is that the case" and the setting steadily gets filled with details that support / justify the authorial fiat. There'll be more detail in my long-simmering social worldbuilding post, but you are on the ball with how the existence of Hell and the way the gods work change things - religion can't really be used as an excuse to gloss over or dress up political conflict for a variety of in-universe reasons

DeleteFantastically done. It was my pleasure to give what little I did towards the making of this piece and the Okavim, even if it was mostly by endlessly babbling about various obscure bits of Jewish minutia.

ReplyDeleteThis is great--a wonderful Hannukah gift, and a great translation of Judaism into a fantasy context as opposed to the usual shit.

ReplyDeleteAm Yisrael Chai!

Well let's continue the tradition I guess,

ReplyDeleteAvodat would be a monotheist (or otherwise extremely henotheistic) panentheism with strong mystic and esoteric traditions and

Who knows what new insights might be found (this is propably only missing question mark so it's not really the traditional thing)

Fixed, thank you!

Delete